It was a simple drive twelve miles north this morning to get to Skokie for Algis Budrys's memorial service. Laura was unable to join me so I went alone, and I found when I arrived at the funeral home that there was no one there I knew. Actually, I did meet Ajay's dear wife Edna back in 1985, but I wouldn't have expected her to remember that brief occasion all these years later.

I don't do very well in crowds where I don't know anyone—heck, I can get intimidated in crowds where I do know people—so I sort of slinked around at the back of the room, feeling somewhat like an intruder. Two display tables helped me occupy myself. One was covered with an arrangement of various editions of Ajay's books. The other displayed a selection of interviews with and articles about him, both from print sources and online. On a widescreen television ran a slideshow of photos of Ajay and his family.

The service began not long after I arrived, and I found a seat toward the back. There were fifty or sixty people in attendance, I would estimate, and the number of chairs for everyone was almost exactly right. A pastor spoke for a few minutes about Ajay's greatness as a husband and a father and a writer, and offered a prayer. Then she turned the time over to Ajay's sons.

Jeff shared remembrances and appreciations of Ajay he had gathered from people online over the preceding few days. Among the poignant, funny, and just simply factual snippets he read, I was startled to hear a line I had written in a brief post on Monday. Tim expressed his good fortune at being able to spend many of his adult summers with his parents' house as a home base, and shared an observation an associate at a Renaissance fair had made—that no wonder he seemed so even-keeled, with parents who had always stayed together. Dave recounted the last years and final days of Ajay's life, when despite setback after setback, Ajay had remained cheerful and become even more of a sweet man. All three sons credited their parents with giving them the space to do their own thing—as long as they did something. There was also much talk of Ajay's prowess as a bicycle builder and mechanic—the boys grew up having by far the best bikes around, at a time when 10-speeds were still exotic—and stories like the time he singed his eyebrows off cleaning bike parts with gasoline.

After the boys spoke, Edna offered a few words in tribute to Ajay's humor and wit. She also recounted how, when they were young and living in New Jersey and playing a regular penny-ante poker game with Fred Pohl and others, they would all pay their poker debts to one another first anytime a check for a story arrived in the mail.

Next the pastor opened the service to remembrances from anyone who cared to share them. We heard moving and amusing stories both, from people like the massage therapist who worked with him the last three years of his life, the neighbor who eventually went into politics with Ajay as a close supporter and publicist, the young man to whom Ajay was a surrogate father figure, the director of the Writers of the Future contest who had worked with him for 24 years, the friend who first met Ajay in the '50s in the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society, the younger cousin whose family were fellow immigrants, and more.

Finally, after some internal wrestling, I stood up. You might not know it if you've heard me speak, but it terrifies me to talk in front of a group unprepared, especially a group of strangers. But none of Ajay's students had spoken up yet, and I thought at least one should. What I said, more or less, was that despite only really knowing Ajay for a few weeks during the summer of 1985, he'd had a profound influence on my early development as a writer, as he no doubt had on thousands of others. I said that what I carried with me was not just the serious lessons about writing that he imparted, but also the demented childlike glee in him that would manifest at the oddest times.

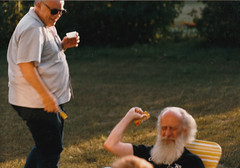

I recalled the epic water fights of our Clarion workshop, and Ajay squaring off against Damon Knight with water guns at our final barbecue. What dangerous opponents they were to any who crossed them! And I recounted a scene that is seared into my brain, how when Ajay spied a blue stuffed rabbit that seemed to show up as a Clarion mascot year after year, he got a demonic look in his eye, hissed, "I ... hate ... that ... rabbit!", and proceeded to bite, kick, and bludgeon it into oblivion. "If you knew Ajay at all," I said, "you can imagine what a startling sight it was to see him jumping up and down on that stuffed bunny."

What I learned from this, I said, was to try to remember to keep a spirit of fun about me, even when engaged in work what I consider to be serious work. I managed to get through my two minutes without resorting to a tissue, though it was a close thing.

After a couple of more remembrances, the mourners filed past the open casket one last time—Ajay looked about as good as anyone I've seen in that situation, with a very short, neatly trimmed white beard—before retiring to the parking lot. Edna thanked me for what I had said, which put me at something of a loss for words.

I had to be back home, so I didn't join the procession to the cemetery for the interment, but I trust it was as lovely and bittersweet a ceremony as the service at the funeral home. I will leave it to others to remark on Ajay's importance to the field of science fiction, but I can only remark right now on his importance to my science fiction. I'll never forget him because he was the first person to, with authority, give me serious reason to think I might really be capable of becoming a professional writer. In his curmudgeonly way, he told me I wasn't close to there yet, and he certainly let me know it was going to be a difficult process, with only a small likelihood of flashy rewards, but he let me know I had the potential.

One last thing I will never forget is how, on the last day of Clarion, Ajay brought to me a copy of the souvenir book we students had made with a selection of our stories, and almost shyly asked if I would sign it. Of course, all of us were signing one another's copies, like yearbooks, but there was just something in Ajay's approach to asking that made me feel like a king. I was seventeen, and he was a Golden Age giant, but he made it seem like those designations didn't matter. And they didn't.

I've started scanning some of my photos from Clarion '85, including what I think are some nice ones of Ajay and Edna.